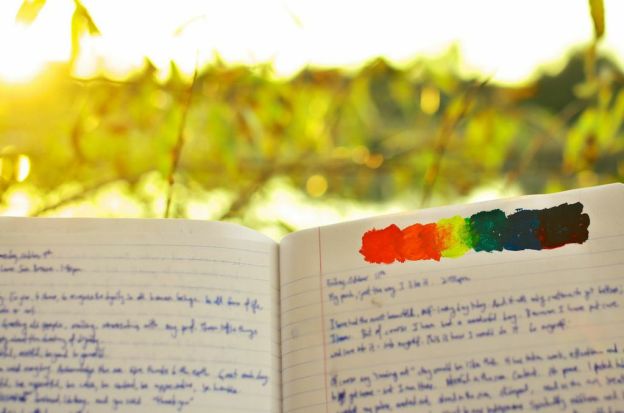

On a warm autumn Friday exactly a year ago, I came out to my friends and family on Facebook. It was the middle of the morning. I sat down at my desk, opened my laptop, and took a deep breath. Today is October 11th, National Coming Out Day, I wrote. In the past few months, I have been able to come out to an ever-widening circle of family and friends, something that had been a huge source of anxiety, denial, and self-doubt for me. […] Today, I am coming out because I want to live honestly, visibly and proudly – first and foremost to myself, and then to others around me. (To see the full text, click here). I pressed “post”, closed my laptop, and didn’t check my phone, Facebook, or messages for the next fourteen hours.

My day was a buzzy, beautiful blur, filled with a deep and effusive feeling of warmth that never left. I went on a solo forest walk in the sun, had introvert time at my favourite coffee shop, and got red-wine happy-drunk with close friends. At 2 a.m., I finally logged onto Facebook. I could not believe what I saw on my screen. The post had over 500 likes and 80 comments.

Ok, pause.

As National Coming Out Day is today, I’d like to invite folks who are queer, questioning, and allied to take the time to reflect on the politics of coming out, and consider its wider context. (For shorthand purposes, I’m going to use the word queer as the umbrella term for LGBTQIA2S+, which stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, trans*, queer/questioning, intersex, and two-spirit, as well as identities that exist beyond the acronym.)

We live in a society that privileges people who are white, cisgender, heterosexual, male, able-bodied, thin, non-Indigenous, and middle class. This occurs systemically (in institutions that govern our lives) and locally (in our interpersonal interactions). Coming out, therefore, is safer for some queer folks, and less safe for others.

To all the folks thinking about coming out today or any other day – power, strength, and visibility to you. Stay fierce. But know this: there is a broader context of systemic and localized oppression in which we are all situated, and there is pride, discomfort, and silence embedded in this context. This is something I wish I had considered in my own process of coming out — but more about that later.

So, in no order of importance, here are seven reflections on ‘coming out of the closet’:

Ps. Links have been embedded for further learning, please check them out!

1) On coming out as a perceived ‘goal’:

Coming out is not always the goal for queer people, nor should it be. For many folks, coming out is not necessarily safe, expressed, or desired. Some people do not to come out for privacy reasons. Some people do not come out because they are – or never will be – ready. These choices are all totally valid. Your identity is your own, and your (non-)coming out story should take whatever path you wish.

Note: ‘Coming out’ can also occur in other forms, such as in reference to disability, sexual assault survivorship, and mental illness.

2) On coming out as a perceived ‘choice’:

Coming out is not always a choice. Sometimes we are forced to come out. Sometimes we are ‘outed’ without our consent. Sometimes we are shamed for not being ‘visible’ and ‘proud’. This is an unfair burden that we have to navigate on top of the difficulties (and joys!) of being queer.

3) On cisgender and ‘mainstream queer’ identities:

We live in a heteronormative and cissexist society – a society that privileges and normalizes straight and cisgender folks, while stigmatizing and oppressing queer and trans folks. Thus, coming out is generally less safe for people who identify as trans, asexual, intersex, two-spirit, bisexual, pansexual, and non-binary gender (including genderfluid, genderqueer, and agender)*. These folks face erasure, ridicule, and pathologization of their identities. 57% of trans people are disavowed by their families upon coming out, and 65% have suffered physical or sexual violence at school or work. These statistics are even more extreme for folks who are, for example, racialized, Indigenous, disabled, and/or poor.

As well, many folks are forced to explain their sexuality/gender identity on top of having to come out. Many others experience oppression through language, as their identities exist outside the colonial confines of English – at the shortcoming of the language, not the person. Even in social justice spaces (and of course, in mainstream culture), these people are often excluded and rendered invisible. Some examples include the trans-exclusionary politics of TERFs and the frequent erasure of asexual identities.

*Edit: This list is not at all exhaustive. And thank you to Savannah Pulfer for notifying me about the omission of non-binary gender identities.

4) On racism, colonialism, and queerness:

We also live in a society that privileges and sustains white dominance. Coming out is therefore generally safer for white folks, and less safe for queer and trans folks who are mixed-race, Indigenous, and/or people of colour (QTMIPoCs). In addition to being hypersexualized, exotified, and fetishized, QTMIPoCs are disproportionately affected by the realities of assault, homicide, poverty, unemployment, workplace discrimination, homelessness, and incarceration. For example, in 2011, people of colour comprised 87% of all anti-queer murder victims. Just one example is Islan Nettles, a young black trans woman who was violently murdered because of her trans identity, appearance, and race.

In white settler societies such as Canada, the United States, and Australia, colonization is intimately linked with homophobia and transphobia. European colonizers denigrated and shamed two-spirit people (essentially, those who embody both a masculine and feminine spirit), who had been respected and honoured as visionaries, medicine people, and healers in many Indigenous communities. Today, two-spirit, queer, and trans Indigenous folks are confronted with the colonial products of homophobia and transphobia within and outside their communities, in addition to other innumerable and ongoing colonial violences.

To learn more about QTMIPoC experiences, resistance, and creativity, check out this, this, this, this, and watch this!

5) On intersecting oppressions:

As community educator Kim Katrin Milan says, “we are layers, not fractions.” Our identities live in relation with, not isolation from, each other. In addition to the cissexism, transphobia, transmisogyny, racism and colonialism discussed above, many of us experience additional compounding oppressions, such as ableism, sizeism/fatphobia, mental health stigma, xenophobia, border imperialism, homonationalism, sexism, and classism. Coming out is less safe for folks navigating intersecting oppressions.

6) On heteronormativity and homonormativity:

Coming out can reinforce heteronormativity (essentially, the dominance of heterosexual people in Western society), as it positions queer people as anomalies who have to declare ourselves as different. We often have to appease straight folks and compromise our identities to be ‘accepted’. In other words, sometimes we have to act as the ‘palatable queer’ and subscribe to tropes of queerness in order to be understood by mainstream society. This is called homonormativity. Both homonormativity and heteronormativity do not actively dismantle homophobia and transphobia, as they continue to uphold heterosexual privilege while allowing certain queers (read: white, settler, cisgender, able-bodied, middle-class) to join ‘the club’. This occurs at the expense of queer folks who are, for example, racialized, Indigenous, trans, Palestinian (see: pinkwashing), poor, and undocumented.

7) On internalized shame and stigma:

‘Post-coming out’ is not a magical pot of rainbow gold at the end of some arc in the sky. Some days are still really hard. As queer people, we are taught not to exist. We are taught not to celebrate our desire or non-desire, not to hold our lover’s hand in public, not to have children. Often, this manifests in repression, denial, and internalized shame – all of which we carry in our bodies. Our individual journeys towards self-acceptance are not always easy, and coming out isn’t necessarily the culmination of this process. For many of us, coming out is just one step in an ongoing battle against internalized homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and anti-asexuality – to list a few.

Ok, unpause.

After checking my Facebook that night, I spent the next hour crying into my hands. I never thought I could be out to over 500 people, let alone see the tangible support from 500 people, but there I was: out to the world, out of my closet, vulnerable yet affirmed. It felt odd to derive so much emotionality from a Facebook status, but at the same time, the post bore witness to the magnitude of support I was so, so lucky to receive.

However, I come from a place of privilege when I speak about my positive experiences with coming out. The reality is that my community’s support, as well as my ability to come out in the first place, directly stems from my cisgender, thin, able-bodied, class, white-invoking, academic, citizen status, settler, English-speaking privileges. In other words, my privileges made coming out a (comparative) breeze for me. I did not have to think about being disowned, alienated, or homeless. I did not have to think about being ridiculed, questioned, or invalidated. The day after, I wrote a follow-up post to try to be accountable to these privileges – but in the end, I was still coming from a place of safety and validation.

I now realize that my coming out moment had the potential to devalue or negate other people’s experiences with coming out. It had the potential to make some folks feel uncomfortable, silenced, or upset. As I look back, I feel a complex mix of emotions about my coming out experience: happiness, shame, pride, sadness, and, well, ambivalence. It’s a complicated thing that I’m working through, and it feels really vulnerable to write about.

Ok, deep breath.

Coming out is a complex subject. It can be heavy. It can be silencing. But it can also be liberating and freeing. It’s important to talk about these experiences too (though always important to remember for whom coming out can be liberating and freeing).

As someone who spent many years struggling with internalized homophobia and shame, I never thought I could reach a place of self-care with my identity. My journey was not easy. My internalized homophobia manifested in externalized homophobia, which I unfairly inflicted on some people very dear to me. I am still trying to pick up the pieces, and I owe so much of my ongoing process of self-acceptance to their loyalty and patience.

And yet it has become easier. It has only been a year since I left my suffocating yet simultaneously comforting closet, and there have already been so many beautiful-shy-raw-thrilling experiences: from timid queer moments to proud queer moments, from waste-face make-outs to butterfly kisses, from one night stands to tender first dates, from tinder laffs to okcupid bffs, from nervous isolation to softpowerful new communities. I have mixed feelings on how I came out, but I have absolutely no regrets about coming out. Today, I am proud to identify as a queer woman of colour, and it feels good to honour and nourish all the elements of my layered self.

The point of me sharing my story is to say this: if you’re not ready to come out, or never will be, that’s totally cool. If you decide to come out (or have come out), that’s cool too. But please remember this: coming out can hold different meanings for different people – liberation, dignity, uncertainty, discomfort, visibility. Our experiences as queer people are intricately connected with, and affected by, each others’.

Happy National Coming Out Day!

Thank you to Lauren Kimura, Emilee Guevara, Kim Katrin Milan, and so many others; without you I do not know where I would be. An additional thank you to Arielle Baker, Jezebel Delilah X from Black Girl Dangerous, and the folks at The Talon for their incredible editing help.

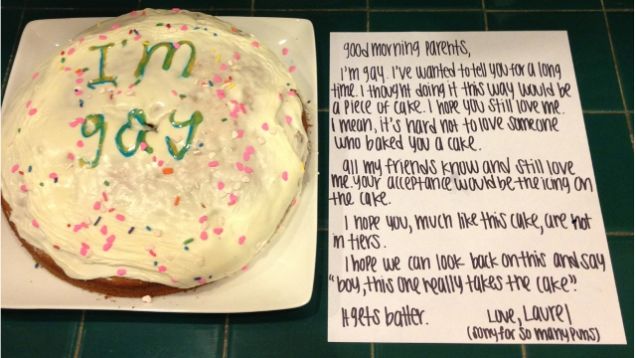

Ps. How cute is this! (see below)