my english teachers in china assigned me with the name jane. under most circumstances i’m okay with being called jane, though sometimes I can’t help but think of the more famous english janes (Eyre, Austen, Goodall, Grey), all of whom surely owned its meaning – “Yahweh is gracious/merciful” – far better than i, a chinese heathen, an ‘oriental’ psychiatric problem, someone’s asian foot fetish fantasy strolling in the dark through (white) knight street in need of a ride home, a ‘flawed subject,’ a literature major, an experimental poet, a community organizer, an editor at The Garden Statuary, and an editor here at The Talon.

There’s a popular series written by a British children’s author under a name that keeps her gender private, but I confess I haven’t read most of her books. Being a heathen as shameless as any other, I insist on the importance of Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events in contemporary children’s literature (almost as though that other series never existed).

A Series of Unfortunate Events

I wouldn’t be the person I am today if it weren’t for those thirteen books, the accompanying audio-books, and in particular The Unauthorized Autobiography of Lemony Snicket, where all the questions you’ve ever wondered about the world of the Baudelaire orphans and the villainous Count Olaf could be answered.

For the uninitiated, A Series of Unfortunate Events is a young person’s introduction to anti-oppression through the lens of three unlucky children’s persistent struggles to survive an unforgiving world. Unlike most introductions to anti-oppression, difficult words are frequently defined, such as in Chapter 3 of The Miserable Mill: “’Cacophony’ a word which here means ‘the sound of two metal pots being banged together by a nasty foreman standing in the doorway holding no breakfast at all’” (30). Or here, in Chapter 9 of the same book:

Oftentimes, when children are in trouble, you will hear people say that it is all because of low self-esteem. “Low self-esteem” is a phrase which here describes children who do not think much of themselves. They might think that they are ugly, or boring, or unable to do anything correctly, or some combination of these things, and whether or not they are right, you can see why those sorts of feelings might lead one into trouble. In the vast majority of cases, however, getting into trouble has nothing to do with one’s self esteem. It usually has much more to do with whatever is causing the trouble – a monster, a bus driver, a banana peel, killer bees, the school principal – than what you think of yourself. (115-16)

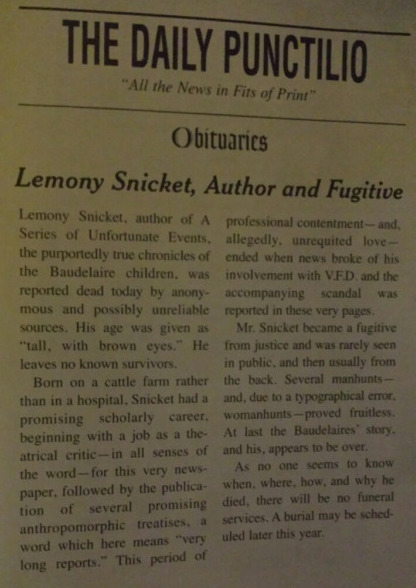

We find out in The Unauthorized Autobiography that Snicket is a theatrical critic, fugitive from justice, and man who needs your help. We learn of his struggle to tell the truth in a world with media outlets as reliable as Fox or Sun News.

No autobiography, though, is ever only about its subject. A letter Snicket writes to his sister reads,

“My Dear sister,

I understand how desperate our situation has become, but it is dreadful enough for people to have to read about the Baudelaires. I cannot imagine who would be brave enough to help them.

With all due respect,

Lemony Snicket” (192).

The last sentence suggests a difficult relationship between reading (or writing) about something, and creating change. If Snicket, one of the only people paying attention to the Baudelaires, hasn’t the courage to help them, who would? Whose responsibility is it to help the Baudelaires, whose lives are filled with violent neglect and malice at the hands of adults – so-called grown-ups – who are given power and have all intentions of abusing it? And what of those well-intentioned grown-ups like Snicket, so out of touch with their current situation?

As solemn as it may sound, this letter acts as a foil by contrasting Snicket to the incredibly resilient, self-sustaining Baudelaires. Readers implicitly know that A Series of Unfortunate Events is a tale of continued survival.

Meanwhile, The Unauthorized Autobiography documents Snicket’s own resilience while growing up, and further affirms children’s (the readers’) agencies through its hypertextual form. The book is a juxtaposition of letters, photographs, secret documents, newspaper clippings, and other facsimiles that readers must make sense of themselves. Its non-linearity encourages creativity, its multiform presentation suggests a desperate attempt to construct a document of primary sources, one that fails, on the surface, to represent a coherent sense of self.

For me, The Unauthorized Autobiography is most importantly a satire. The core of its world is as cruel as our own, but Snicket does not let us get away without laughing: at our foolishness, at our gullibility, at how seriously we take ourselves. That complex, ridiculing engagement, of course, should remind us that reading is also a complex action, rooted in all other actions. How would we be able to resist oppression day after day, year after year, without being able to interrogate cruelty with and through laughter? After all, laughter is transformative.

I look forward to working with The Talon, where I hope to produce work as funny as The Ubyssey’s.